What Makes a Story Shocking?

Stories can do wonderful – or terrible – things to an audience, so why aren’t there any guidelines for authors? Answer: because for every conceivable rule, we can find valid exceptions. I have thought long and hard about the ethics of storytelling, but without arriving at consistent rules. Some friends of mine, on the other hand, are waging an honorable battle to eliminate violence and explicit sex from popular entertainment.

I call their struggle honorable because it’s intended to protect society, and we do need protection. Yes, there is far too much violence and vulgarity in movies and television. But a censor will have a terrible time if she tries to be even-handed and consistent. If she rules out violence, there goes Hamlet! If she rules out passionate sex, there goes the Song of Solomon! If we say that sometimes sex and violence are okay, we cannot say what makes them so. One legendary judge, ruling on a case involving pornography, supposedly said, “I can’t define pornography, but I know it when I see it.” Probably that’s the only answer, but it’s far too imprecise to fit within the rule of law. Perhaps we can clarify it slightly by bringing in the notion of “context.”

Ethical-emotional criticism, which I admire and even attempt to perform, assumes that the value of a story is measured by its answer to this question: How should human beings live? Stories give us tips on how to flourish in our mortal existence. They can elevate our souls to higher aspirations or leave us feeling dirty. Yet no quantitative analysis of content can explain why a particular story has the former, rather than the latter effect. The meaning of a particular word or an act is determined by the larger context.

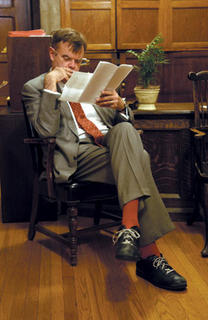

I was reminded of that fact a few days ago by hearing that a radio station in the midwest had cut off a broadcast by Garrison Keillor, my favorite entertainer. I adore the man, though I’ve never met him. (See photo.)

It seems that new broadcasting regulations have been established to prohibit vulgar language. Mr. Keillor allegedly uttered the word “breast” on one of his shows and was summarily banned for it. Fortunately, scores of listeners protested and the authorities soon restored him to good standing in radio land. I did not hear that particular show, but I’ve listened to at least 200 hours of his programs and I know his style. Sometimes Keillor actually does mention shocking topics — yet if I were asked to name the single nicest person in the world, I might pick him — or at least his radio persona. (Obviously, a person might be sweet on the air but a tyrant in real life. I have no idea what Keillor’s dark side is like, but I presume it’s no worse than mine.)

The puzzle to explain is this: Keillor can tell a story about, say, a taxicab passenger with catastrophic diarrhea, and the audience will enjoy it. Nobody will consider it off-color, but if anybody else told it, we all would. Context makes all the difference. Keillor loves his characters and explores their predicaments and shortcomings with benign warmth. He never expresses hostility or even dismay (except briefly after George W. Bush and the other “vandals” were returned to power in Washington). His characters are so natural and ordinary that we can easily imagine being in their shoes. The Lake_Wobegon stories are especially touching, endearing — including memories of his own that he shares with us.

Once, for example, he described his tenderness upon watching his five-year-old daughter singing Christmas carols in a chorus for the first time. There he sat in the audience, reminiscing about the occasion when she was conceived. (I gasped. Surely he’s not going to tell us about that! But he went on in his mellow way.) It had been in a hospital. He had leaned against the wall watching as a technician named Ron carried out the procedure. And here was his little girl now — singing in a Christmas pageant. His memories, his feelings seem so simple and normal.

There are sordid stories all around us. Sordid, sleazy, artificial. I wish we could replace them with Garrison Keillor’s stories, which always are pure. Yet there’s probably no situation so shocking that Keillor cannot tell it in a way that allows us to empathize, to feel for the characters, perhaps to laugh, but always to wish them well. How does he do that? I think it springs from his avuncular decency, the unstudied charity of a compassionate man. The meaning of anything depends on context, on the intention behind it. There can be no objective measure of depravity or goodness, no scientific tabulation of instances of ugliness or beauty. We just have to know it when we see it.

2 Comments:

Excellent!

My principal is on my back because I tell my kids stories. (My class theme this year is What is Your Story?

Having trouble convincing her of the worth of stories like... Stealing hubcaps with Tony Valentine... http://consilience.typepad.com/teachers_lounge/2005/08/what_is_your_st_1.html.

I'm sure she worries that other kids will copy the hubcap thief. And sometimes they do. (There's a heck of a lot of research showing that people imitate violent or anti-social movies and TV shows.) But much depends on the context -- the intent of the storyteller. If the most popular kid in your class brags about stealing hubcaps and nobody calls him on it, his story may actually influence the others. Presumably, since you are there reflecting on his stories, that's where your own wisdom comes in. Thanks for sharing. This is a HUGE issue and we need to think about it a lot.

Post a Comment

<< Home