Getting Smarter about Ending Hunger

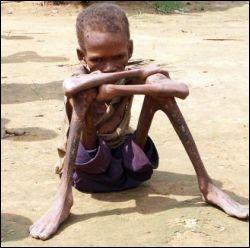

How can developed countries intervene constructively in situations of extreme hunger, such as those prevailing in Niger these days?

This question differs from the one that I’ve had to address here in the preceding blog entry, when a woman questioned, not how, but even whether to intervene. I find it emotionally troubling to read comments to my posts that argue against responding at all to hunger in other countries. I never meet such people in real life, but obviously they are out there someplace, for they chime in on the discussions that I initiate here. Don’t they realize that every day, more than 16,000 children die from hunger-related causes--one child every five seconds? More likely, they just don’t care. Well, I do.

The effectiveness of governance is one crucial determinant of food security. As Amartya Sen and Jean Dréze have shown, wherever the government is a democracy, famine never occurs. When it seems to be impending, citizens have enough power to force the regime to take action. Often hunger is a result of warfare, which interrupts the production and distribution of food and causes poverty by shifting expenditures to weapons instead of social services and infrastructure.

Hunger is rarely caused by food shortages. There can be hunger even when the granaries are full if the local people don’t have enough money to pay for food — as sometimes happens to farmers who cannot sell their produce at a good price.

The isolationists argue — partly correctly — that development aid is sometimes spent in counterproductive ways. However, the solution is not to cease offering aid altogether, for Pete’s sake! Instead, in this imperfect world, where we often make dreadful mistakes, we must simply to take responsibility for the choices we make that affect others, and proceed as actively as if we could be perfectly prescient.

The first idea that springs to mind in a situation of widespread hunger is to send food to the villages where people are starving. This is a particularly appealing idea when our own farms are producing a huge surplus. Nevertheless, development experts have learned that this is often a poor approach. One of my favorite journalists, The Globe and Mail’s own Doug Saunders, has recently (Sept. 10, p. F3) described the lessons that have been learned through experience about how to stop starvation.

What happens when we send bags of food is that the people eat some of it and sell the rest at the market to buy other things that they need. Then when the harvest comes in, the farmers cannot sell their produce because the people already have received all their families need — for free. “Sometimes,” writes Saunders, “the worst thing you can do for starving people is give them food.”

Nevertheless, Canada has often done so — both out of a misplaced attempt to be charitable, and to get rid of our own enormous surplus. The cost of shipping grain is, in itself, so high that it makes little economic sense, even so. Saunders quotes Mark Fried of Oxfam Canada as saying, “It would be cheaper, and a lot better for the victims, if you just dumped it all in Montreal Harbour and used the shipping money you saved to buy grain in Africa.”

Oxfam is leading the way toward a different approach: using the cash donated as aid to buy food grains grown within the crisis-stricken country, so that the farmers there benefit. However, there’s a downside to this too: The aid donations may drive up the local grain prices so much that the impoverished local people cannot pay for it anyway. Therefore, the UN’s relief workers have to monitor the situation carefully. They must not give food away for free, so they make “loans” to the poorest families — and only to those who would otherwise not be able to buy food at all.

At the same time, the UN watches to make sure they neither undercut the price of local farmers nor raise their prices above the affordable price. To keep this from happening, they sometimes buy the grain from another nearby country that is more prosperous. And as soon as the local harvest comes in, they cut off the free food, so the ordinary market resumes functioning normally.

Obviously, this is a tricky process to balance, but we’re learning. It is possible to use development aid either stupidly or wisely and — thank goodness! — wisdom is increasing.

1 Comments:

"Instead, in this imperfect world, where we often make dreadful mistakes, we must simply to take responsibility for the choices we make that affect others, and proceed as actively as if we could be perfectly prescient." I certainly agree with the first half of this sentence, but the last half ("as if we could be perfectly prescient") scares me. Can't we "proceed actively" & still proceed with a caution that recognizes our human lack of foresight? When I play blind, I always slow down & feel my way forward (even in a room I am familiar with)!

Post a Comment

<< Home