On Being a Pessimist

Pessimism ... is, in brief, playing the sure game. You cannot lose at it; you may gain. It is the only view of life in which you can never be disappointed. Having reckoned what to do in the worst possible circumstances, when better arise, as they may, life becomes child’s play.

— Thomas Hardy (1840–1928), British novelist, poet.

One has to have the courage of one’s pessimism.

— Ian McEwan (b. 1948), British author.

Optimism doesn’t wait on facts. It deals with prospects. Pessimism is a waste of time.

— Norman Cousins

I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.

— Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), Italian political theorist. in Letters from Prison

Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're going to get.

— Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks)

I just offended a friend of mine by calling him a pessimist. I don’t like to be rude, but he is planning his life around an expectation that can only be called the “worst case scenario” about the survivability of life on this planet. Still, when people think I’m characterizing them unfairly, I stop and give it some thought. That’s what this blog entry will do.

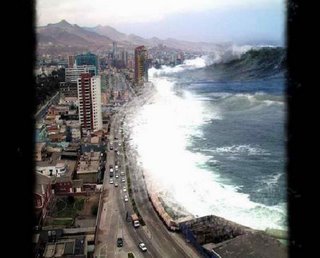

Pessimism and optimism are about the way we organize ourselves with respect to an uncertain future. When the future is unmistakable — as in the situation recorded by this image of the tsunami of December 2004 — there’s no room for either pessimism of optimism. It is obvious what will shortly happen.

But climate change is not so certain, and it makes a great deal of difference how accurately we anticipate it and revise our plans so as to enable the human species to survive it. My friend insists that pessimism, optimism, or realism here have nothing to do with personality. The orientation depends on whether one looks closely at the best scientific evidence. And one is obliged to be as realistic as possible, if not indeed pessimistic, and plan for the worst scenario, for false optimism will kill us all.

And yes, one can make a case for that hard-nosed attitude. It’s better than the opposite, but neither one is ideal. As Al Gore put it, lots of people go directly from a state of denial that there’s any problem to a state of despair and defeatism, without going through any intermediate phase of activism. My friend is not one of those. He remains a committed activist, even while holding out the gloomiest possible prognosis of the future.

None of us can be sure what’s coming. We are in the situation of Forrest Gump, who noted astutely that “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” This open-mindedness has its benefits, but we do need to prepare, and so we need to gauge the probabilities and act accordingly.

But for us, life is not really like a box of chocolates, for, to some degree, how we act will determine what happens.

At the conclusion of his wonderful radio series, “Sustainability and the Future of Humankind,” (http://www.yorku.ca/ycas/) David V.J. Bell suggests that our pessimism or optimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we are optimistic, we will recognize the various opportunities for saving the situation, whereas if we are pessimistic, we will not attempt to do much, for everything will appear impossible. Worse yet, our pessimism will affect others so they do not take action either. Instead of pessimism, we must face hard possibilities without being daunted. And not just one possibility. Futures are multiple, plural.

Yet not everyone agrees that pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Some people take pride in being extra-brave by recognizing futility when it seems to lie ahead. Like Ian McEwan, they believe that “One has to have the courage of one's pessimism.” They may even believe that their pessimism prepares them best for hard outcomes, as Thomas Hardy apparently assumed, to gauge by this comment of his:

“Pessimism ... is, in brief, playing the sure game. You cannot lose at it; you may gain. It is the only view of life in which you can never be disappointed. Having reckoned what to do in the worst possible circumstances, when better arise, as they may, life becomes child’s play.”

Whether pessimism is a self-fulfilling or a self-negating prophecy depends, for some individuals, on whether they depend on having hope. Some people summon the fortitude to keep going only when can reasonably anticipate a good outcome. Indeed, a philosopher of my acquaintance wrote a book about the necessity of having hope. I never agreed with her opinion. I personally don’t operate on the energy of hope, nor do most activists whom I have known over the years. If I know I am going to perish, I want to die “with my boots on,” pursuing to the end the goals and ideals that I believe in. I recall that in her film “If You Love this Planet,” Helen Caldicott said that in her final moments, before going to meet her maker, she wanted to know that she had done her best. This attitude (which is neither optimism nor pessimism) is the best answer to the false optimism, the denial, that keeps many citizens from participating actively in the task of saving the world.

I believe that the optimum moral response is to keep testing reality and appraising it as accurately as possible, while still acknowledging that one’s appraisals are partly a matter of personality. But to make one’s personality traits a fatal obstacle is as unhelpful and untrue as to adopt fatalism on any other basis. As personality traits go, one’s pessimism or optimism are not decreed by nature but are matters that one can decide. As Norman Cousins said,

“Optimism doesn’t wait on facts. It deals with prospects. Pessimism is a waste of time.”

And, as Antonio Gramsci wrote, “I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.”

I salute the will of the optimists, for they encourage others by setting an example by their own wise dealings with prospects.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home