Who Runs the United Nations?

The leaves are just beginning to turn in the Gatineau Hills on the Quebec side of Ottawa. The Group of 78 traditionally gathers there at a resort for a weekend every fall to listen to invited speakers and contemplate current affairs. This year our first evening was especially pleasant because Joe Clark was with us.

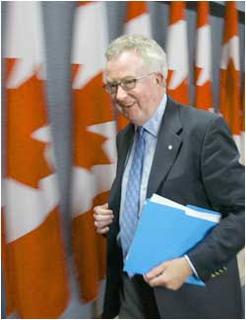

As all Canadian readers know, Clark was twice the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party (while it was still genuinely progressive) and briefly served as 16th prime minister. When the PCs merged with a more right-wing party, he left the country to teach a while at American University in Washington, D.C. This fall he’s back in Ottawa, but no longer holding political office. Now he has time to sit up late, chatting with us, then rise early to sit in a session before heading back to town.

This year, despite the beauties of nature that surrounded us, the group was in a sombre mood, mostly because of the recent failure to reform the United Nations. There was nothing whatever to celebrate, and the speakers seemed to be trying hard to reveal a few bright potentials in the gloomy stories they told.

Fortunately, a self-designated scapegoat emerged among us, prompting (thank goodness) one energetic debate. A young woman, Melissa Powell, had just described her work with the Global Compact, a group of businesses that have come together at the United Nations at Kofi Annan’s urging. In a Davos conference, he had proposed a partnership with corporations who would develop codes and principles of conduct to help develop the planet in constructive ways.

The Group of 78 was too polite to criticize Melissa, though I could sense an unspoken skepticism about her organization. Given the prevailing view of corporations as overly powerful, the Group suspects the business world — especially when it is ensconced in the very office of the secretary-general himself. Yet our Group listened quietly to her presentation; it was not a member but the next speaker who interrupted the courteous silence with a provocative harangue.

Michael Hart is an economist at Carleton University. His post is funded by a business firm that had acted improperly, he said, in the very act of sponsoring his professorship. The only thing a corporation should do, he said, is make money for its stockholders. It should not be donating money to other projects, whether worthy or unworthy. On the same reasoning, he flatly criticized the businesses that constitute the Global Compact. There are laws to regulate companies. Though firms must obey those laws, they should not exceed the demands of the government or take a leadership role concerning ethics, environmental management, or other matters of public policy. They should stick to their own function: making money.

Oddly, most members of the Group of 78 shared Hart’s misgivings about the Global Compact — but for diametrically opposing reasons. They doubted that businesses would ever really behave as good global citizens, even if they signed a document promising to do so. Hart, on the other hand, was complaining about these corporations for showing too much ethical self-restraint. He swaggered about, speaking in the most provocative manner possible — barely this side of rudeness. And his audience — previously so gloomy — began to snort audibly and roll their eyes. He was getting everybody’s goat. There were more socialists in the room than I had realized, and the rest were red-blooded anti-globalizers, bent on bringing corporate capitalism to heel.

But Hart had launched his provocation by showing how greatly standards of living had improved during our own lifetime in areas where capitalism was functioning. The only hope for the rest of humankind, he suggested, was to embrace the market and let businesses make money precisely by finding out what people need and want, and producing it. He smiled at the objections he was hearing, even from other economists.

I raised objections too — but not exactly the ones other people were pointing out. I agreed with him that capitalism has raised our standard of living and extended our life expectancy. Nevertheless, it seemed to me, there are many different interests in society and corporations certainly don’t necessarily meet them all. We need structural ways of making businesses more accountable. For one thing, all their holdings and plans should be completely transparent. We should be able to go to a web site and find out where each business is buying up rain forests or cattle or mineral mines. Moreover, each board of directors should be required to include members representing their employees, consumers, environmental organizations. and other civil society organizations whose interests are affected by its policies. Yes, probably at least 51 percent of the decision-making body should be accountable to the stockholders, but a sizeable percentage should be democratically accountable to the public. “And with such arrangements in place,” I said,“go ahead and make all the money you want.”

Professor Hart was horrified and said so. The Group of 78 was not horrified but rather befuddled. They had never heard this proposal before. They knew what socialism looked like and what capitalism looked like — but what would this be? It was radical, yet also conservative. They were shocked but not hostile. I think most of them felt a little embarrassed.

Hart evidently had fun that afternoon and so did I. But Joe Clark had left hours before, having had a bit of progressive conservative fun of his own, in a Canada much like that of the old days.

2 Comments:

big?????

Sorry, but I don't understand your question -- or maybe it's a comment.

Post a Comment

<< Home