Peace is Breaking Out All Over

Ask people what would be the best thing that they can imagine happening in the new year and most people would probably reply: "peace.” Then they’d add something about how hopeless are the odds of getting it. But that’s mistaken. We are getting more peace all the time. So now you have something to celebrate on New Years Day.

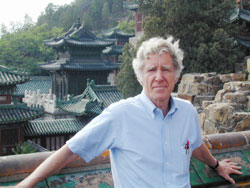

The problem is, not many people are aware of these changes. In part it is because of the inadequate methodology of counting wars and instances of peace. For example, Dr. Andrew Mack (see photo) used to head the Strategic Planning Unit in the office of Secretary General Kofi Annan – a role the included planning for human security around the world. He was disturbed to realize that the United Nations does not keep a database on wars and threats to human security, so it was sometimes hard to be sure what the trends were. Few states keep accurate records about their own crises. Indeed, peace research institutes also have methodological problems. They often have to rely on the reports of journalists for counting wars and acts of civil disorder. As we all have come to realize, the press is not even-handed in what it covers, so this source is far from ideal. Moreover, the states where human rights violations occur most frequently often dispute the evidence proving these grim facts.

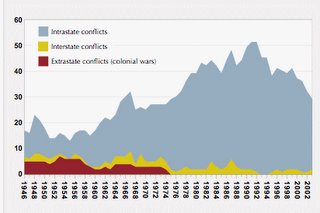

Despite these methodological problems, it has become quite clear since the early 1990s that the frequency and gravity of political violence has been declining sharply. The wars that do take place are almost all within states, rather than between states, and even those have been decreasing in number and severity.

Dr. Mack now heads the Human Security Centre at the University of British Columbia’s Liu Institute for Global Issues. His organization has begun to compile annual reports on human security, drawing heavily on data collected at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, which counts human security by using a wider range of indicators than most other databases.

His centre’s 2005 Report on Human Security declares that:

• During the 1990s, after four decades of steady increase, the number of wars being fought around the world suddenly declined. Wars have also become progressively less deadly since the 1950s. In 1992, more than 50 armed conflicts involving a government were being waged worldwide. By 2003 that number had dropped to 29.

• Civil wars (intrastate conflicts) increased after World War II until 1992, but have declined sharply since then.

• The international arms trade declined in dollar value by 33 percent between 1990-2003.

• Military coups have declined 60 percent since 1963, when there were 25 actual or attempted coups around the world. By 2004, there were only ten, all of which failed.

• Because of the decreasing number of wars, the number of refugees dropped by about 45 percent between 1992 and 2003.

The explanation for these changes must be, to some extent, speculative and theoretical, yet most of us will readily accept the majority of the researchers’ arguments. They point to two main determining factors: the decline in colonialism (which not only involved violence against the indigenous populations but stimulated violent resistance) and the ending of the cold war, which had kept the world polarized in a prolonged state of ideological belligerence. To be sure, the two sides refrained from direct war themselves, but they instigated and paid for large numbers of proxy wars, especially in the poorest countries. It is still the poor countries that experience the most violence, but nowadays the wars are internal rather than international, and are often between non-state actors, such as tribes or ethnic communities fighting against each other.

I am not satisfied with two of the explanations proposed in the Human Security Report. The first is their claim that the cold war system of mutual deterrence actually succeeded in preventing a live nuclear war. It is never possible to know what would have happened if what did happen had not happened. In that sense, Mack and his group have a perfect right to claim that deterrence worked, since indeed no nuclear bombs have been explored as weapons since Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, most experts who know how these systems work call it a miracle that no such catastrophe has occurred accidentally. The risks have been completely beyond any rational justification and remain inexcusable to this day. If we do not eliminate nuclear weapons they will eventually eliminate us.

The second argument that I cannot fully embrace from this report is its relative dismissal of the importance of democracy as a cause of the declines in war. The authors do point out that democratic states almost never go to war against other democracies. They further point out that “The number of democracies increased by nearly half between 1990 and 2003 while the number of civil conflicts declined sharply over the same period.” However, they do not credit democratization for this enhanced condition of peace. Their reason is that, whereas fully-fledged, well-established democracies have few wars, states that are only partly democratic have numerous wars. They argue that the number of partial democracies has increased along with the number of full democracies, thus possibly offsetting the advantages conferred by democracy overall in the world. To make that claim (which may perhaps have some validity) one would need to present mathematical tabulations analyzing the data. They offer no evidence on the point, however, and I would not want to accept their conclusion without strong evidence.

They do, however, reach one conclusion that seems insightful and valid. They show that the ending of the cold war liberated the United Nations to become more effective in working to prevent wars and to restore peace after wars. The vast upsurge of activism is credited — rightly, I believe — with much of the progress that the world has made. It happened becayse of activism on the part of the UN and other multilateral bodies, and also on the part of non-governmental organizations. These interventions often work – and we should be reminded more often that they do work. We have many reasons to rejoice.

So on New Years Eve, let yourself go. Rejoice!