Encounters with Berkeley Souls

Every day here I meet at least one memorable Berkeleyan who is struggling to reconcile apparent spiritual contradictions.

Take Arthur, for example — a graduate student in biochemistry who is finishing his Ph.D. research on the enzyme that unzips the double pairs of DNA helixes to allow cells to divide. He’s dedicated to promoting nonviolent resistance against dictatorships. We talked for several hours in a coffee shop about how to spread Gene Sharp’s alternatives to war. He’d tried to get some UC peace studies professors to endorse his nomination of Sharp for a Nobel peace prize but one of them told him that Gene had done a lot of damage in the world by separating nonviolence from spirituality. According to Gene Sharp, you don’t have to be devout to practice nonviolence. That view had appealed to Arthur, who is apparently opposed to religion, which he equates to “superstition.” He’d balked at Gandhi's writings just because it was so linked to spirituality. Arthur disclosed these opinions only after I had acknowledged that I am religious in my own way, though I agree with Gene that spirituality is not a prerequisite for nonviolent action. Now at least I know the dimensions that our future conversations can take, and what issues I will allow to pass without comment.

Or take the elderly black woman jazz singer at the BART station. I had gone to the theatre to see “Nine Parts of Desire,” in which one woman plays nine different Iraqi women. It was a stunning, harsh drama set in the ruins of Baghdad and it ripped me apart with its portraits of bitter fortitude. As a political protest, it worked brilliantly. I was walking back to the hotel with my soul in tatters. But then I heard a voice that made me stop. There was a tall, gray-haired black woman in shabby clothes strumming her guitar and singing praises to God in an unearthly coloratura. “Precious Lord, Hold My Hand,” her clear soprano voice said, audible all the way down the block. I shivered in ecstasy and tears came to my eyes. A young man with a bike had stopped too, and we listened, marveling through two songs. People were throwing bills into her open guitar case. I wanted to give something back to her too. She finally ended on a high tone and opened her eyes, meeting my gaze. “Thank you,” I said. “It was magnificent.” Then I walked on slowly. The play had spoken to my heart, but her song had moved my soul.

Or take the young Israeli artist I met at the Shambhala Center last Sunday. We both had shown up for meditation instruction and talked during the break. Both of us signed up for this weekend’s complete program, so we went out for tea last night after the initial Friday meeting. He has just finished a masters degree at the art college. His thesis was a room-sized installation that you wander through, looking at signs that are posted along a path. The first signs are political. The middle ones are aphorisms about his personal life. The last ones are blank. “Emptiness, Buddhism,” he explained and then added, “Postmodernism.” The message is that there’s nothing to say anymore.

“That’s nihilism,” I replied. “I don’t like postmodernism.”

He acknowledged that he doesn’t like it either – except that he accepts one of its points: that there is no truth. There’s only your truth and my truth, nothing beyond that.

“I believe in science,” I said. “They just discovered a new planet today that is pretty close to the size of earth. That’s an objective truth. Some people know more of the truth than others do, and I think that’s a fine goal to pursue. Science is about getting closer to the truth. That’s what my professor said: Karl Popper.”

He did not recognize the name, which is natural. Popper died about ten years ago. Time moves on. We debated in a half-hearted way about whether there’s truth. He doesn’t believe much in science anyhow. He’s becoming more spiritual instead and is trying to unlearn about half the theories he studied in art school. They were just blah blah blah. He’s going through psychotherapy now as part of his unlearning. His psychotherapist advised him to take up meditation. His wife is working toward a doctorate in agricultural development economics, and they are expecting a baby. He phoned her and spoke briefly in Hebrew. Then we went back to the topic of science and religion.

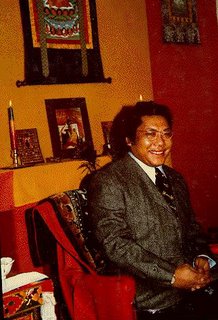

He doesn’t believe in religion, but he’s becoming more “spiritual.” He’s taking the Shambhala class because it’s secular. Chogyam Trumpa, the maverick Tibetan founder, (see photo) wanted to create a practice for people who don’t want to become Buddhist. In my young Israeli friend’s mind, Shambhala is not a religion, though it is in my mind. It’s a matter of definition, and my definition of religion is losing ground to his. A religion, in his mind, is a set of rules about how to behave. He had despised religion because the “religious” Jews he knew originally are super-orthodox fundamentalists who have vast political power in Israel. But now he is becoming more “superstitious,” he said, as he learns that not all religious people are as rigid as those Jews. At least he is open to spirituality, even if not to religion.

I don’t like that new definition. I always define religion in terms, not of doctrines, but of its vital function: to help people find themselves in a meaningful, intelligently organized, beneficent universe. I don’t have any fixed beliefs but I have faith: the conviction that ultimate reality (though human beings can never understand it) is good. The trust that I’d be satisfied if I could understand it. The hope that I may get closer to the truth. Whatever people do to sustain such faith is religion. To him, however, that’s "spirituality," whereas religion is a narrow set of beliefs for rigid people. His definition is winning. Here’s what Wikipedia says:

“Some individuals draw a strong distinction between religion and spirituality. They may see spirituality as a belief in ideas of religious significance (such as God, the Soul, or Heaven), but not feel bound to the bureaucratic structure and creeds of a particular organized religion. They choose the term spirituality rather than religion to describe their form of belief, perhaps reflecting a disillusionment with organized religion (see Religion in modernity), and a movement towards a more "modern" — more tolerant, and more intuitive — form of religion. These individuals may reject organized religion because of historical acts by religious organizations, such as Islamic terrorism, the marginalization and persecution of various minorities or the Spanish Inquisition…”

Or take the young woman of Indian ethnicity with whom I had lunch today during our break from meditation. She’s a quiet person who came here from Houston to take a three-year training program in acupuncture. Only slowly did other biographical details emerge. She already has a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Berkeley. At first she had worked on a project aiming to develop a quantum computer, but her advisor had given up that project so she had changed into working on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. She had not been happy with the social interactions in her work group and had not got along with the adviser well enough to win references or grants for a career in that field. Besides, she concurs with her adviser: She shouldn’t try to do that kind of work. She doesn’t have it in her. But the adviser called her research "deep and excellent" and gladly endorsed her Ph.D. degree.

I was shocked. Why would she give up a career in science for an unverified practice such as acupuncture? Because she doesn’t believe in science anymore. She recommended a book called The End of Science, which argues that there’s no more to find out. We’ve done it all. Yes, there’s engineering; that has a future. Planetary exploration does too. But basic_science doesn’t. As an undergraduate she had taken not only science courses but also a minor in Asian religion. She’d studied everything available about Asian medicineand now she wants to go into it professionally. She believes in it a lot more than she believes in Western science. After all, medicine is an art, not a science. It’s based on intuition more than knowledge.

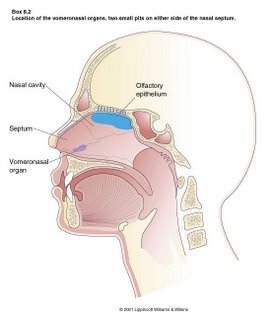

“What about chi?” I demanded. “Can anyone even prove that it exists?”

“No,” she replied smoothly. Nobody will ever be able to measure it. You can experience it but you cannot test it empirically. But she showed me a book she was studying. It was a skimpy thing written in high school level English, with simple, non-technical drawings of meridians and spinal columns. This is her faith. Maybe it’s also her religion. Anyhow, it’s her substitute for science.

I said I felt sorry for her. “A mind is a terrible thing to waste,” I quoted. She agreed that it was appropriate to feel sorry for her.

These are some souls inhabiting Berkeley nowadays. It’s the best place in the world to spend time with strangers. I don’t entirely agree with any of them, but their hearts are right out there for me to see – sometimes even to touch.