I’m going to make a prediction:

George W. Bush’s presidency will go down in ignominy. You can tell this by watching how

American TV is turning against him. We’ve reached a tipping point. Things are being said onscreen today that would not have been said six months ago. This is, in part, because the media follows

public opinion, and Bush’s appeal has declined sharply, according to the polls – but the

media also

influences public opinion, and what television is saying about the war is going to give Bush his comeuppance. I’m not talking primarily about the newscasters, though you can see changes there too, but about

television drama, which is far more powerful than people realize. And right now, TV dramas are looking favorably on the idea of

peace.

I don’t watch much TV, so my sample is hardly scientific, but I did see episodes of two different shows last week. Neither of them went so far as to question the

legitimacy of America’s role in

Iraq. (That will come at a much later stage.) What they did was criticize the

way the war has been run. They did so in terms of its effect on the soldiers fighting there.

Boston Legal this week ran an episode in which the protagonist, a feisty lawyer in a large Boston firm, takes on the case of a young woman who sues the U. S. Army for lying to her brother in order to

recruit him — then holding him beyond his contract expiry, failing to

train him for the

combat operations that he had to perform, and giving him

inadequate equipment for the job. He was killed, and she wanted her screams to be heard. In the end, the judge couldn’t hold the

U.S. government accountable but he did express admiration to her for accusing them.

The second show that I watched was

Numbers, a regular

crime show in which the protagonist is an

FBI agent. The person initially believed to have perpetrated the crime, a failed terrorist act, turned out to have a fool-proof alibi: He had been in Mexico in a

drug treatment centre when the crime occurred. He was a

veteran of Iraq who had

broken down emotionally and mentally upon returning home and had taken up drugs. Then the real perpetrator is identified by his mention of the 1400 US

soldiers killed in Iraq as the motive for his crime.

(The episode must have been filmed a while back, since the actual number killed has risen to over 2,000 — not counting, of course, the

30,000 dead Iraqi civilians, who will probably

never be mentioned in a US television show.

Our dead soldiers matter;

their dead civilians don’t. That’s just part of the psychology of war.)

Nevertheless, when television drama begins to show the terrible effects of war on American soldiers, George W. Bush had better watch out! Soldiers do undergo breakdowns after experiencing war. And soldiers do get killed there. When television dramas start mentioning those facts, public opinion will follow. And, democracy being genuinely better than dictatorship, some Americans eventually will be held accountable.

Besides predicting the ignominious failure of the Bush administration, I want to point out how we can help make it happen. How can we show Bush up as a disgrace? First, by exposing the fundamental flaw in his

argument for war, and, second, by showing what he should have done instead.

I don’t actually think his justification depended on the lie that

Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. Certainly it also didn’t depend on the neocons’ intention to seize control of

Iraq’s oil and establish American military bases throughout the Middle East. Those may have been Bush’s real motive, but he would never have stated it outright. He always cloaked it in other arguments — in particular by saying that Saddam was a ruthless dictator whom the Iraqi people loathed and would have ousted, had they been able to do so. By going to their assistance, Bush was

bringing freedom and democracy to the Middle East, where all Islamic societies are authoritarian.

Now there are enough holes in this argument to drive a Humvee through. For one thing, Bush is hardly the right pitch man for democracy, having stolen a presidential election at the time and, by now, possibly two. Still, his argument has a certain aura of decency and, to a considerable extent, it is true. The Iraqi people were indeed oppressed, as are citizens in most other Middle Eastern countries. It is indeed honorable, in my opinion, to help other societies free themselves from repression. In fact, I would accept his argument — but with two important qualifications.

First, we

should help other people free themselves – but the struggle has to be

theirs, not ours. Second, their struggle must be nonviolent and the support we give them must also be nonviolent. Those two qualifications would certainly have precluded the invasion that Bush undertook and any others like it. (It would not rule out UN peace enforcement operations under Chapter Seven of the UN Charter, but nobody claimed that Iraq qualified for intervention under Chapter Seven terms.)

Anyway, it will be quite a while before there’s a real political debate in the US or even in Canada about the two qualifications that I have proposed — that the overthrow of a dictatorship should be carried out by the affected population themselves, and that it must be nonviolent. The reason there will be no debate is that public opinion believes such conditions to be completely unrealistic. No dictator could be overthrown by the people themselves nonviolently. War is necessary because

nonviolent resistance against tyranny is impossible.

I will borrow an answer from the pacifist economist

Kenneth Boulding: “Whatever is, is possible.” In other words, if something has taken place, you can no longer claim that it’s impossible. And populations have indeed got rid of totalitarian rulers and tin-pot dictators through nonviolent means.

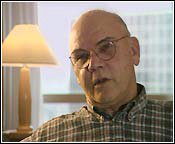

But let’s not minimize the challenge. In saying that it’s possible, I don’t say that it is necessarily easy. People sometimes try it and fail. In 1989, all around the world people turned Communist dictators out of office, sometimes without bloodshed. But also in 1989, the Chinese Army killed hundreds of protesters in Tiananmen Square and crushed their movement. Just as wars are won or lost on the basis of wise or unwise strategies, nonviolent movements are also won or lost on the basis of strategies. It takes skill and know-how to plan a nonviolent resistance movement, with or without the support of friends abroad. In fact, the US government itself has supported several nonviolent movements, such as the one in Serbia that overthrew Milosevic and the Orange Revolution in Ukraine. Some people disapprove of that, but it doesn’t bother me a bit. What does bother me is the American government’s readiness to go to war. For example, the U. S. bombed the heck out of Serbia, trying to get rid of Slobodan

Milosevic; they failed. Yet a year or so later, they gave $40,000 to assist a group of young Serbs called “Otpor,” who invited Colonel Robert Helvey, a superb instructor in nonviolence, to train them. (See photo.) Within months, they had ousted Milosevic, without shedding a drop of blood. Then they started training democratic opposition movements in other countries, such as

Georgia, helping them get rid of corrupt rulers. Lebanon and Kyrgyzstan followed suit.

This is not a rare situation; people sometimes have to adopt nonviolent methods because they are more effective than warfare.

And in the most obvious sense, these nonviolent movement won. Yet that’s only the start. Once you get democracy, you have to struggle hard to keep it. God knows, even in good old democratic Canada, we are not unfamiliar with corruption and inefficient government. Today Serbia and Ukraine are free but they still have plenty of problems.

So nonviolence doesn’t guarantee everything. Life remains challenging. But if you ask me, that’s a good thing. Peace sounds boring; it suggests the absence of struggle. Peace is what you rest in when you’re dead. But real peace isn’t easy or boring — partly because conflict continues. As long as there are human beings on this earth, there will be conflict. But war? No, we can stop that.

I think Iraq could have been liberated nonviolently by the Iraqi people themselves. There were, in fact, expatriate Iraqi citizens who were preparing to do so, but never got the chance. They should have been supported by free societies. The Norwegians, for example, are now supporting the Burmese democracy movement, most notably by

broadcasting informationinto Burma that could not be disseminated easily by Burmese inside the country. I hope Canada’s government-funded organization,

Rights and Democracy, will give the same kind of help to people seeking to free themselves from dictators. That is what it was set up to do. And in doing so, we will accomplish our other main goal: to show what Bush should have done instead of going to war in Iraq.