Fictional Characters Can Change the World

The message of my book can be summarized in one sentence: Fictional characters can change the world.

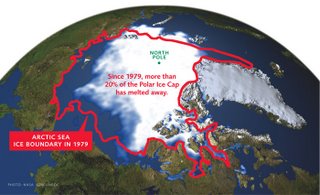

In fact, we require fictional characters to change the world because apparently we can’t do it ourselves. Consider this. In 1983 I started working as an activist to rid the world of nuclear weapons. Lots of my friends did so at the same time. Guess what: 23 years later, there are still enough nuclear weapons to destroy civilization. In fact, nowadays we have additional looming dangers that also threaten human survival: global warming, the end of oil, pollution, the depletion of natural resources, the hole in the ozone, the extinction of species – you name it. We’re failing, friends, and we’ve run out of time.

So what can we do to meet these challenges? We need to create a world-wide social movement in which people change their personal habits and urgently demand structural changes in society too.

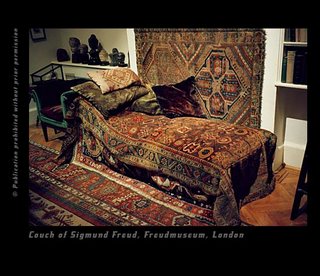

People know the facts. It’s not a matter of educating them, for they are already well informed. The problem is, knowledge and rationality are not enough. What is missing is something completely different-- motivation. Psychologists tell us that cognition and motivation involve different parts of the brain. Motivation doesn’t come from information, it comes from feelings – sentiments, affects. It comes from caring. It comes from emotional human relationships.

Ordinary human beings are not very emotional. We laugh only about fifteen times a day. We cry only a couple of times a week, if that. We hardly ever scream with terror or rage. We fall in love only a few times in our whole lives. That unemotionality is mostly a good thing. It allows us to be steady, reliable individuals. But it means that we’re not very good at stirring up each other’s feelings. Emotions are disruptive. For example, recall the last time you fell in love. Remember how it put a swerve into your whole life course, making you re-think who you were and what you wanted to be and do? Strong feelings do cause new motivations. Nothing else does.

If we are going to save the world, we need to motivate billions of people by making them care passionately about something – care enough to break out of their old patterns and demand that the whole world change with them. You and I can’t do that. I can educate students and magazine readers – I spent my whole career doing that – but I cannot motivate billions of people. I can't communicate with so many people, and when I do, they don’t react to me with strong feelings. Nobody has fallen in love with me for ages. So how are we going to touch billions of human lives? Who can do that?

Answer: characters in movies, novels, and – especially -- television series Almost everyone watches TV. Maybe not you or I, but others do. The World Cup soccer matches are seen by 4.5 billion people. Every week about 1.1 billion people watch a defunct TV show called Baywatch, which I have never seen once. And the remarkable thing is that ordinary people experience more emotional connection to these fictional characters than they do to their own close friends and family. Good scriptwriters and actors can make us care about characters. You have more intimate knowledge of many fictional characters than you do about your own son or daughter or spouse.

Our everyday lives are casual, matter-of-fact, and pragmatic. Fictional characters, on the other hand, are expressive and highly motivated. That’s a requisite for drama. To write a play, you create at least one character who fervently wants something that he doesn’t have. The rest of the play is about how he tries to get it. If it’s a good drama, we’ll identify with him. We’ll empathize; we’ll feel his emotions along with him, we’ll root for him to get what he wants. We’ll make his motivation into our own – at least temporarily.

But the impact of emotions may also be sustained. We take aspects of that relationship into our own motivations. By empathizing with the characters we learn how to act in situations like the ones they have demonstrated. We don’t have to learn from our own mistakes; we can learn from theirs. And what kind of things do people learn?

Occasionally, the scriptwriters deliberately set out to influence us. For example, a Harvard public health professor brought together 250 TV writers and asked them to popularize a new notion: the so-called “designated driver.” Soon the term was in the dictionary and polls showed that most people had actually performed the role of designated driver. In the United States, drunk driving fatalities dropped by 50,000. What a lot of lives were saved by such a simple, obvious social innovation!

Mostly, however, fictional characters exert their influence inadvertently. For example, all around the world, birth rates are dropping in places where theoretically they had not been expected to drop. There will be one billion fewer human beings on the planet than had been projected a few years ago, apparently because people are watching small families on TV and deciding to limit their own family size. Likewise, in 1989, people around the world got rid of communism, virtually without bloodshed. They had studied the movie Gandhi a few years before and had taken lessons from it. The film made us care about the Mahatma, and he inspired us. If they’d make a movie about successfully getting rid of nuclear weapons, we might get someplace with that project too.

Emotions have visceral bodily effects. They can make you sick or healthy. If you watch the battle scene in Saving Private Ryan, your circulation will be reduced by 35 percent for an hour. If you watch the comedy Something About Mary, your circulation will be improved by 22 percent for an hour. Your immune system is affected too. As Norman Cousins famously established, laughing at old Marx Brothers movies can heal supposedly fatal illnesses. The emotions – positive or negative -- that we experience vicariously by empathizing with fictional characters are physiologically identical to those arising from real life situations. They have the same health effects, good or bad. We need to be more aware of the impact of the movies and television shows that we choose to watch.

Relationships with fictional characters also influence our political, social, and spiritual sensibilities. We can enhance global culture by fostering the production of television series about outstanding, lovable characters working hard to solve the world’s problems -- protecting the rainforests, making peace instead of war, eliminating nuclear weapons, educating girls and women in refugee camps, and so on. Because we come to care about such characters as we follow them throughout several seasons, we want them to succeed, and we’ll try to help them. Every such series can have a web site where the audience can discuss the global issue that its characters are working to solve, and where NGOs can recruit new members.

Of course, what I’m proposing is a daunting challenge, especially in a world where advertisers decide what stories will be broadcast, and where cultural products are considered mere commodities. We must change the storytelling industry — not by censoring bad productions but by fostering good ones. Cultural products are subsidized everywhere, but we can change the basis of the subsidies. Instead of just paying for those shows that we want to consume for our own pleasure, as we pay for our own personal shoes or computers, we need to think of culture as environment that we all share and that we are responsible for protecting. For example, although I rarely go to the ballet or to national parks, I want there to be ballets and parks in my society, so I’m glad to subsidize them.

That suggests a way to support shows that inspire and motivate whole populations. Let’s allow every taxpayer to allocate, say, $200 per year of her taxes to a fund for the kind of independent cultural productions that she believes in supporting. We can influence billions of human beings by supporting productions that are gripping, entertaining, and fun. The cultural environment is our most powerful human resource. Let’s stop wasting it.